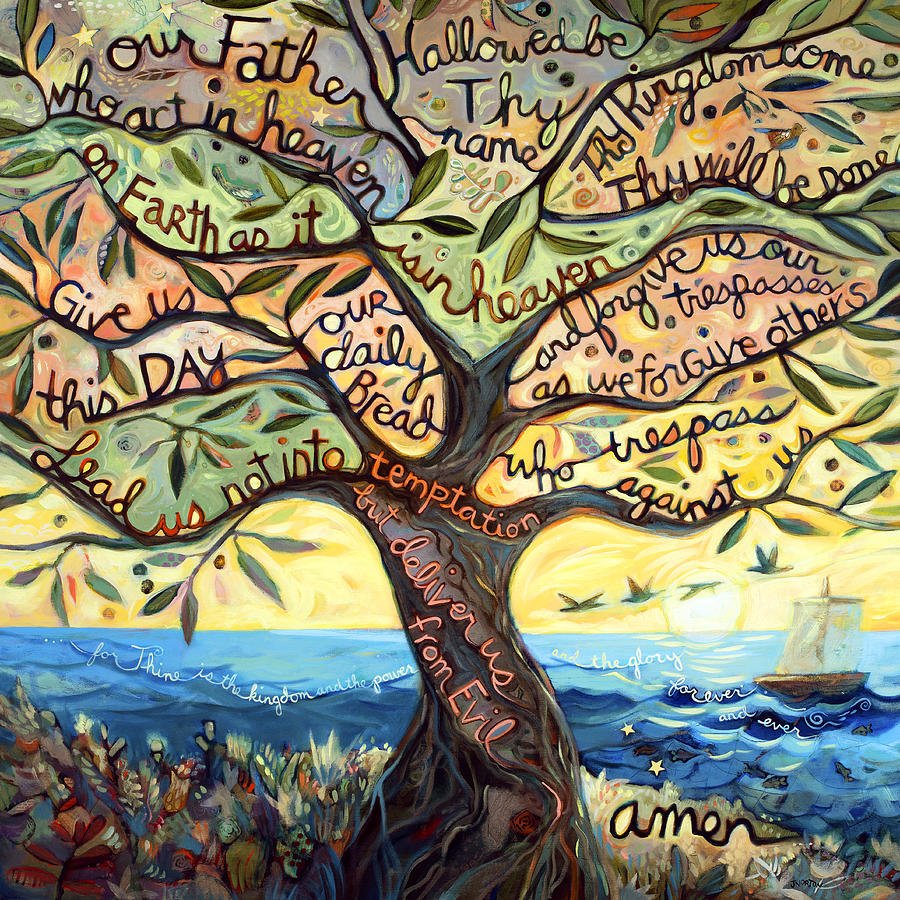

Our Father Painting by Jen Norton

….by the help of your mercy, we may be always free from sin and safe from all distress.

These words form part of what is formally called the embolism, the short prayer said by the priest after the recitation of the Lord’s prayer at Mass. The intent of the prayer, which dates from the early Church, is to provide a gloss or commentary on the last petition of the Our Father, “Deliver us from evil.” In the most recent English translation, a more literal rendering of the Latin text from which it is taken, the words “may we be … safe from all distress” replaces the freer translation dating from the time just after the Second Vatican Council, “protect us from all anxiety.” In both instances, the Latin word is perturbatione which we might use in English in its verb form, “to be perturbed”, but rarely as a noun.

My interest is not really in linguistics, but in considering, especially in the times in which we are living, what it means to be delivered from all anxiety or made safe from all distress – and if there are different shades of meaning in the two words. For all the years that we prayed to be protected from all anxiety, my association with that expression was primarily psychological and I remember feeling, even as I was reciting the prayer, that “it’s good if you can get it.” But here’s the rub. Should we not be wary, anxious even, about minimalizing the prayer in this way, making it into an ideal worthy in itself, but beyond any realistic hope of realization? After all, the prayer does not say, protect us from undue anxiety or undue distress, but all anxiety and all distress.

So, a few things to consider. Is there a difference intended by the shift from anxiety to distress? And what grounds are there for asking to be entirely freed from either of them? It should be noted that the first petition in the embolism is to be “always free from sin.” Is the intention to draw out a causal connection between being freed from sin and being freed from distress, or, taken together, are they intended to fill out what it means to be “delivered from evil?”

If the second of these is true, and this is how I read it, then anxiety and distress are to be included among the evils that beset us. They are “perturbations” that rob us of peace and the security of knowing that our lives are, always and at all times, in the hand of God. The regular and fervent prayer to be free from them is to ask, at the same time, for that childlike trust that God is looking after us and that God wants to bring about our good.

Accordingly, distress may better convey the intent of the prayer than the more psychologized anxiety. In our normal way of speaking, anxiety speaks to the internal disturbance brought on by threats to our self-preservation. This includes not only threats to our physical well-being, properly speaking, but also the perceived need to take things into our own hands, as in “Martha, Martha, you are anxious about many things.” Distress is more closely related to sadness, to whatever may disturb our equilibrium, our spiritual balance both from within and from without. For as long as it lasts, it makes it more difficult to center ourselves in God’s love.

So much for fine distinctions. The prayer for deliverance from all that separates us from God finds its meaning in the truth of our being children of a loving Father who brought us into being and whose providential care sustains every moment of our lives. In the face of all that may disturb us, remaining firmly rooted in that truth, living it out with full awareness, is the key to our Christian vocations. Let us take courage from the saints, who bear witness not only to the possibility of this deliverance but to the joy that comes from allowing God to take charge of our lives.